Who, What, Why: Will soaring temperatures affect the tennis at Wimbledon?

- Published

Temperatures at Wimbledon this week could reach an all-time high. How might this affect the way tennis is played, asks Jon Kelly.

On Wednesday, temperatures at the tournament are expected to reach a high of 32C - and they could go further, exceeding the record 34.6C set in 1976. When the heat stress index - a measure that factors in air temperature, surface temperature and humidity - exceeds 30.1C, the All England Club's Heat Rule, which allows women players to take breaks, comes into effect.

These conditions are far from unusual in tennis. The 2014 Australian Open was played in temperatures of 42C. But regular Wimbledon watchers may notice very subtle differences.

On a tennis court, it's not just a matter of the ambient temperature being high - this is exacerbated by the lower level of air flow in enclosed courts, direct sunshine and the heat from spectators. When it comes to rackets, "you would expect the string tension to drop a little bit", giving the players a little more control over the ball, says Andy Harland, head of the Sports Technology Institute at Loughborough University. High air pressure associated with high temperatures would tend to slow the ball down through the air. But more importantly, says Harland, the drier ground makes for a harder surface that would have the effect of speeding up the game slightly.

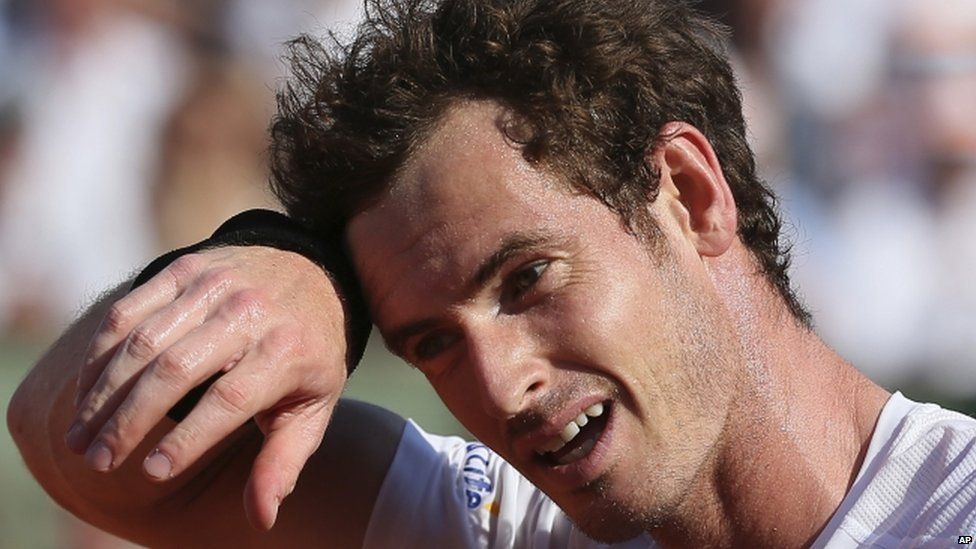

But by far the most significant factor will be the way the players react to high temperatures. Their bodies will generate a huge amount of heat. Their heart rate increases as the body pumps blood from the muscles to the skin in order to sweat. "For the same effort they will have to work a lot harder," says Steve Faulkner, an expert in exercise physiology at Loughborough. Although they might be acclimatised to such conditions, the performance of elite athletes will still be affected, he adds.

A player can produce up to three litres of sweat an hour, more fluid than the body is capable of replacing over the course of a five-hour match, according to Carl James of the Environmental Extremes Laboratory run by Brighton University's sports science department. All this would tend to slow the players down. "They are aiming to reduce the heat that they are producing," says James. "They might be more selective about the points they are fighting for."

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.